|

HOME

THIS Page

NEWS

PHOTO

SHAIKH ZAYED

ABU DHABI

TUNISIA

AZZAMAN

ARTICLE

AL KHALIJ

CONTACT

SOMALIA

LINKS

GUEST BOOK

PAGE

Custom4 Page

Shopping Page Page

Slide Show Page

Whats New Page

|

|

|

|

|

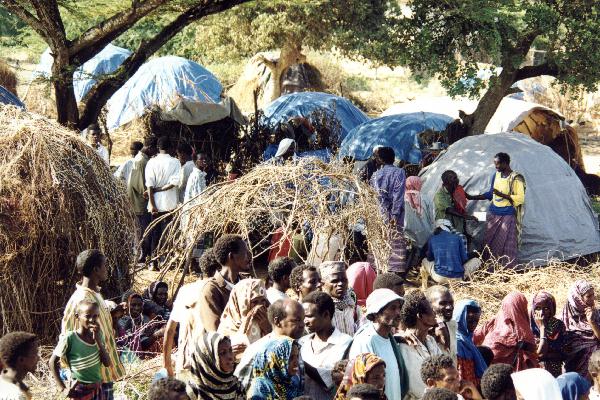

Six months after the withdrawal of the international peace-keeping troops from Somalia, the type and level of foreign involvement in Somalia continues to be one of the key-factors influencing the political developments in the country.

Following the toppling of dictator Siyad Barre in January 1991, the allied liberation militias split along clan lines. After a mass-exodus of members of the Daarood group of clans from Mogadishu, the approaching Hawiye militia (USC) split in two sub-factions, one following the hotel-owner Ali Mahdi of the Abgaal clan and another the general Mohamed Farah "Aideed" of the opposing Habar Gedir clan. The capital -- and much of the rural interior -- has since remained divided in spheres of interest belonging to either of these two militias or their allies.

Weakening factions

One of the most remarkable aspects of this southern Somali deadlock has been the shifting character of the followings of Ali Mahdi and Aideed. Both leaders were quick to strike alliances with individual Daarood clans and also forced areas they militarily dominated-- such as the clans in the inter-riverine zone which were brutally conquered several times in 1992 -- to become their loyal supporters. However, the allegiances shift extremely rapidly and even within the Abgaal and Habar Gedir clans, support for the self-appointed leaders is not certain. Some important Abgaal businessmen have throughout the crisis sided with Aideed and, conversely, a leading Habar Gedir general has fought with his militia on Ali Mahdi's side.

More recently, Aideed's chief-financier, Osman "Ato," broke with Aideed and formed a new movement which quickly turned to the Ali Mahdi side for support. The political polarization between SSA (Somali Salvation Alliance) headed by Ali Mahdi and the SNA (Somali National Alliance) headed by Aideed has affected the entire political fabric so that a large number of the smaller factions are now effectively split in to one SSA and one SNA-loyal subfaction.

However, the strength of the factions has dwindled dramatically. With the departure of UNOSOM (UN's Operation in Somalia) and the loss of the large funds they made available in the form of salaries and generous support for various meetings staged between the factions, and given the generally diminishing influx of foreign aid, the factions' systems of patronage and redistribution of loot have begun to break up and the leaders are seriously questioned. For some time after the departure it appeared as if a group of leading Mogadishu businessmen would be able to take on a leading political role, overshadowing that of the factional leaders in the Mogadishu area. The break between Aideed and Ato is but one of many examples of this process. Not surprisingly, Aideed and other factional leaders issued a number of calls for increased international assistance and, unfortunately, even large organizations such as the ICRC and WFP, responded favourably. ICRC's recently appointed Somalia resident had only been in office for a few weeks when he declared the fertile Jubba valley a famine zone. Militia strength and the ability of factional leaders to hijack Somalia's future is a function of the levels of influx of dollars and aid. The more funds that come in, the more likely it is that the artificial factions will be able to continue to cling on to aspirations for power.

Decentralization processes

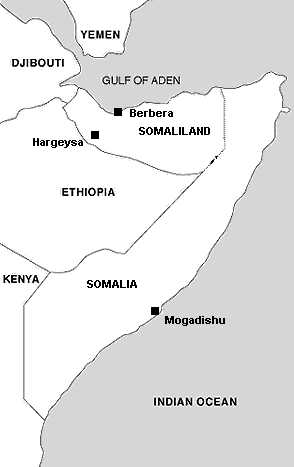

In areas that have received minimal levels of aid and political involvement, quite different processes have emerged. Most notably this has been apparent in the North-western regions which were left largely unattended by foreign donors following the Siyad's overthrow. In 1991 the area seceded from the rest of the country assuming the name "Somaliland Republic." Since then clans of the area have been engaged in an impressive series of conferences engaging continuously widening spheres of clan elders, professionals, intellectuals and modern politicians. In 1993 a bicameral parliament was established and a president elected. While clan-based hostilities occasionally flared and interrupted the gradual process towards normalization, the most serious blow towards Somaliland's relative stability was inflicted by UN's acting representative Lansane Kouyte who paid the person who had lost the presidential elections in 1993 to make a political come-back, enter in an alliance with Aideed and denounce the secession (which he himself had declared). Following this incomprehensible manoeuvre, large-scale armed fighting erupted in and around the capital Hargeysa in November last year and although fighting has since subsided some grievances remain.

In the inter-river area, among the Digil and Merifle clans, a process towards increased political stability and the formation of an administration has gained momentum since 1993. The more than 40 clans in the area has formed a bicameral parliament and declared in May this year their intention to remain autonomous in the event a Somali state is resurrected. The process has united the two strands of the local faction (SDM - Somali Democratic Movement) and combines a modern political leadership with the strength of the traditional leaders. Similarly, the Majertayn clans in the Northeast have since 1992 functioned as a mini-state on their own. A more articulate declaration of autonomy or secession would probably have been expressed a long time ago had it not been for their involvement in the southern port of Kismayo which has spread the SNA/SSA divide to the area and fuelled an internal struggle over leadership. The latter problem was also greatly inflamed by UNOSOM's support to one of the candidates.

|

|

|

|

|

|

These brief examples show that when Somalis are left on their own, they are perfectly able to produce viable and sustainable political institutions. In many areas the present political decentralization is appreciated and provides sufficient security levels for local business and agricultural production to flourish. When foreign aid is delivered in a sensible way as rewards for political achievements rather than in the vain hope to incite it, it can contribute significantly to help further processes of stabilization. Unfortunately, some organizations have continued to seek to create artificial and aid-dependant political institutions in the country, often based on whimsical notions of "grass-roots" or ill-defined ideas on "bottom-up" development. The infamous "district councils" that UNOSOM set up in 1993-94 are still receiving funding from, inter alia, Sweden. Despite two successive missions' finding that the councils are dysfunctional and all but obsolete, a recent UNDOS report (UN Development Office for Somalia) recommends funding the councils in one region only with half a million dollar. Other external actors, such as the UN's special representative, are still eager to see a single unified Somali state reemerge and spares no efforts to discredit or destabilize the autonomous and/or independent areas.

|

|